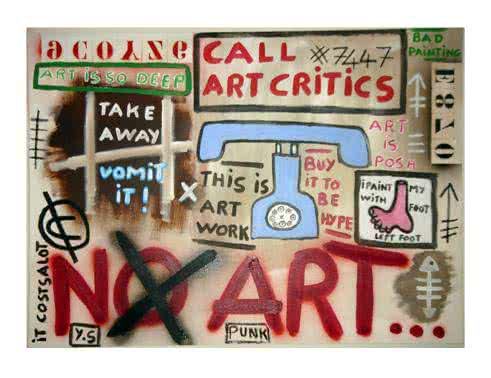

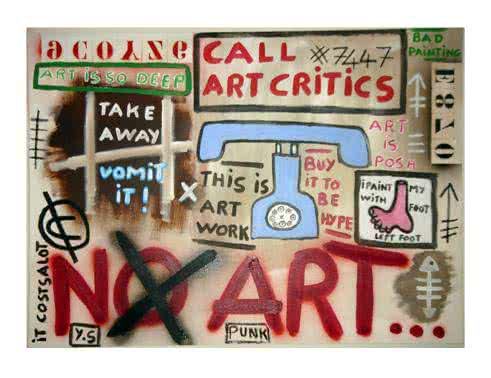

The Childers Group’s next forum, to be held at noon on Friday 18 October at the Gorman House Arts Centre in Canberra, will focus on the role of the arts critic. To get the conversation started, Australian artist Kim Anderson provides a personal account of why a vibrant culture of arts criticism is so important.

The Childers Group’s next forum, to be held at noon on Friday 18 October at the Gorman House Arts Centre in Canberra, will focus on the role of the arts critic. To get the conversation started, Australian artist Kim Anderson provides a personal account of why a vibrant culture of arts criticism is so important.

Where are you, my love? I languish here, yearning for you to cast your discerning eye in my direction. I long to see your face light up with sudden recognition of my genius – which surely must be obvious to you? I send you emails, invitations by post, media releases to which you need only add your valued name before publishing; I try to make it as easy as possible. And yet despite my attempts to seduce you, you are continuously unaware of my existence. Your lack of response is agony to me. Please, I beg you, come to my show, favour me with your words of appraisal and your shrewd nod of approval. Even disapproval. Anything. Just look at me. Acknowledge me. For without you I remain unnoticed, unrecognised, merely wilting into the crowd of countless others like me.

Wherefore art thou, my dearest art critic? What’s happening to you?

You and I, we have a complicated relationship – there’s a bit of love, a fair amount of hate, some amount of disdain, and possibly a lot of confusion involved. I don’t think we’ve ever actually agreed upon your role. Some would argue that your raison d’être is merely a construct of the needs of media industries and academia. Nevertheless, it is fairly evident to me that we need each other – I might timidly raise the possibility that you actually need me more. I can keep making art without you, even if it is unacknowledged and unseen by the vast majority, but you must rely upon the continued creative output of artists such as myself in order to have something to critique. But having said that, and feeling momentarily empowered by the thought, it is my responsibility to create art that is worth writing about. Maybe we’re both at fault here; perhaps I’m just not coming up with the goods. Either way, the glaringly awful truth is that you, the authoritative voice of mainstream institutional Art Criticism (capitalisation deliberate), are in trouble.

Oh, dear, this is such a difficult letter to write. My heart contracts in making these claims; this is only coming from the best of intentions. Bluntly pointing out your particular failures will only lead to further disharmony between us, so I will lightly sketch a picture of some of the issues we are facing.

First of all, visual art needs a response, but I’m afraid that the current one is rather unsatisfying. Recent statistics declare that more people are ‘participating’ in the arts than ever and they are turning up to the blockbuster exhibitions in droves.[1] But where are the audiences for the smaller shows, the more cutting-edge contemporary galleries and artist-run spaces? And where are the critics to inform those audiences, to challenge them to view art and artforms outside the mainstream? Unless such events are part of a festival program and promoted in the corresponding media campaigns, they rarely draw comparative numbers let alone column space.

We must work together if this relationship is to survive and thrive. Marcel Duchamp makes the point that the creative act is not performed by the artist alone, that it is the spectator who ‘completes’ the work of art by deciphering it, interpreting its inner qualification, and bringing it into contact with the external world.[2] You, my dear critic, are a special kind of phenomenon: a spectator yourself, presumably with some expertise on the subject of art, you are also an intermediary between the artist, their work, and other spectators with less insight than you.

This is really a huge amount of responsibility, and perhaps it’s where the vital importance of your role lies. I’m sure we can easily agree on the key elements of good quality arts criticism: yes – providing an informed visual analysis and recounting your experience of the work, providing context for the artist and their methods/concepts/techniques etc., and – the essential factor – stating your opinion and how you arrived at that particular value judgement. Ideally you are conducting an intelligent dialogue with your audience, inviting them to respond by viewing the work in question with additional knowledge and understanding.

But – and this is the trouble – the space for your voice is diminishing, in a rather paradoxical way. In mainstream media lines are being cut from reviews, and arts programs are disappearing from our screens and airwaves at an alarming rate, and yet at the same time the space for discussion in the virtual sphere – the Internet – is increasing exponentially.[3] The old canon is fading away, those familiar names that were once published several times a week with feature-length reviews on weekends. Certainly their word-counts are decreasing until they are becoming little more than brief ‘what’s-on’ listings.[4] Your expert voice is struggling to be heard above the ever-increasing cacophony of bloggers, twitterers, Facebookers, and YouTubers; the new era of Web 2.0 is threatening to drown you out.

Viennese art critic Dr. Gertrude Langer inspecting a local art show, Brisbane, 1940 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

This concerns me, for despite everything I am still on your side. In this age of ‘Like’ and ‘Unlike’ (apparently a verb now) everyone can be a critic – where does that leave your refined art of sustained, meaningful analysis? Once considered a specialised skill, ‘critiquing’ is now something that anyone can do at any time. This new online democracy certainly has its advantages in generating animated conversation and interaction amongst arts audiences, however I feel truly uneasy about a number of issues: the lack of quality control, lack of transparency, and the anonymity. Real names are not required, therefore no-one is accountable. There is even a danger that the seriousness and depth of intellect required for decent critical writing is being parodied and belittled by such tools as the “Arty Bollocks Generator” that spew out incomprehensible jargon-filled rubbish easily mistaken by the unsuspecting and uninformed as genuine commentary.

I urge you to fight against this, even if it means using the very medium that threatens to destroy you. In fact, there is room for both the old and the new. Artists, such innovative folk, have been quick to embrace ‘new media’ (such non-descriptive terminology as it is), but there is still a place for more traditional techniques. We are still drawing, painting, and sculpting more than ever alongside and even in combination with the use of the Web and other new technology. In taking yourself too seriously you have been a species slow to adapt, but this is survival of the fittest and there is no reason why you cannot save yourself. It is obvious that the public want to talk about art, to make sense of their experiences. They need your insight to inform their discussions about what constitutes good, interesting or worthwhile art, so it’s up to you to dive into the fray and provide it by whatever means you can.

Why not follow the lead of artists and negotiate a way for a cross-disciplinary approach to your own artform, a fluid and active engagement between the old ways and the new? The ‘traditional’ spaces could be enlivened by allowing contributions from some of the more well-informed online ‘critiquers’ who, I might venture, tend to visit the more obscure shows. This might not only reinvigorate the arts pages but also allow some of the less-established, unpublished writers to develop their skills and thus revive the whole profession. Or you yourself could grasp the opportunity to stop the humiliating belittlement of mainstream arts criticism by charging head-on into the virtual frontline and elevating the discussion above the level of ‘Like’ and ‘J’.[5] A further challenge could be to take yourself off the well-worn paths to the larger institutions, and wander into a space you’ve never been to before (there are hundreds of them, appearing and disappearing all the time), and hopefully your readers will follow suit. Even – dare I say it – visit the alternative arts spaces in regional areas, and I don’t just mean the public galleries.[6] You – and your audience – might be pleasantly surprised, even excited. Be the one voice that doesn’t just join the chorus of reviews for the ‘big’ shows – a bold move, I know, as it may not necessarily satisfy the higher powers that provide your paycheque, but it may revitalise your profession and bring a newer audience back to the ‘older’ media.

I know you can’t see every single show nor use every method that’s available to deliver your words – you too are only human. I can’t really pretend to rescue you from the crisis you’re facing. After all, I’m just an artist – what would I know? Maybe that’s the heart of the problem in this relationship: it’s not you, it’s me. I’m the one failing to inspire your attention and interest. If that’s the case I am deeply sorry, I will try harder to excite and provoke you. Maybe your expectations of me are too high, but, please, don’t give up on me yet. Let’s smooth this over. Come to my show, just once. If you write about it and I sell a drawing I promise I’ll take you out for dinner.

Notes:

This article was one of two Highly Commended articles 2012 Emerging Arts Writer’s Award, which took the theme, in keeping with Art Monthly’s 250th ‘Critical Lining’ issue (June 2012), of the ‘art of art criticism’. Republished here with kind permission from Art Monthly.

*

A Batchelor of Fine Arts graduate from the University of Ballarat Arts Academy, and a Masters graduate from the University of Dundee, Scotland, Kim Anderson won (for the second time) the Ballarat Arts Foundation’s Eureka Art Award.

[1] As shown in the Australia Council’s well-known study, More than bums on seats: Australian participation in the arts, released in 2010. The blockbusters that the majority of people are ‘participating in’, are generally international in origin and hosted by major public institutions.

[2] Marcel Duchamp, The Creative Act, Lecture at the Convention of the American Federation of Arts, Houston, Texas, April 1957; iaaa.nl/cursusAA&AI/duchamp.html

[3] This is not unique to Australia nor to the visual arts. The crisis in critical writing in general has prompted a huge amount of discussion and concern in Britain and the US, where even larger populations and presumably larger audiences cannot seem to salvage the situation.

[4] Looking forward to the weekend ‘Arts’ pages, so often I find myself disappointed and frustrated by their brevity and triviality, or even worse, their absence altogether.

[5] Blogger/critics such as Nikita Vanderbyl (Vociferous Whimsy blogsite: nikitavanderbyl.com/), and Michelle Kasprzak (michelle.kasprzak.ca/blog) provide more long-form reviews, while better known Australian voices such as John McDonald and Marcus Westbury have gone in the other direction and complement their print contributions with online content: johnmcdonald.net.au and www.marcuswestbury.net.

[6] The arts are thriving relatively unnoticed outside the cities too you know – we’re not all painting rural landscapes (nothing against those who do of course!)